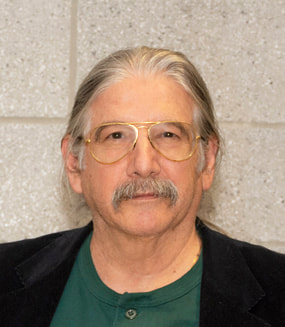

W. D. Ehrhart, one of America’s best-known poets writing about the Vietnam War, is the author or editor of 21 books & the subject of The Last Time I Dreamed About the War: Essays on the Life & Writing of W. D. Ehrhart by Jean-Jacques Malo (McFarland, 2014). Ehrhart is the only Vietnam War veteran ever featured in Vietnam: A Television History (1983), Making Sense of the Sixties (1991) & The Vietnam War (2017) & one of only four Vietnam War poets included in The New Oxford Book of War Poetry. See his biography below and/or more of his Vietnam poems on his Contributing Poet’s page.

W.D. Ehrhart's Vietnam Poetry

Guerrilla War

It’s practically impossible

to tell civilians

from the Viet Cong.

Nobody wears uniforms.

They all talk

the same language

(and you couldn’t understand them

even if they didn’t).

They tape grenades

inside their clothes,

and carry satchel charges

in their market baskets.

Even their women fight.

And young boys.

And girls.

It’s practically impossible

to tell civilians

from the Viet Cong.

After awhile,

you quit trying.

Souvenirs

“Bring me back a souvenir,” the captain called.

“Sure thing,” I shouted back above the amtrac’s roar.

Later that day,

the column halted,

we found a Buddhist temple by the trail.

Combing through a nearby wood,

we found a heavy log as well.

It must have taken more than half an hour,

but at last we battered in

the concrete walls so badly

that the roof collapsed.

Before it did,

I took two painted vases

Buddhists use for burning incense.

One vase I kept,

and one I offered proudly to the captain.

Making the Children Behave

Do they think of me now

in those strange Asian villages

where nothing ever seemed

quite human

but myself

and my few grim friends

moving through them

hunched

in lines?

When they tell stories to their children

of the evil

that awaits misbehavior,

is it me they conjure?

Guns

Again we pass that field

green artillery piece squatting

by the Legion Post on Chelten Avenue,

its ugly little pointed snout

ranged against my daughter’s school.

“Did you ever use a gun

like that?” my daughter asks,

and I say, “No, but others did.

I used a smaller gun. A rifle.”

She knows I’ve been to war.

“That’s dumb,” she says,

and I say, “Yes,” and nod

because it was, and nod again

because she doesn’t know.

How do you tell a four-year-old

what steel can do to flesh?

How vivid do you dare to get?

How explain a world where men

kill other men deliberately

and call it love of country?

Just eighteen, I killed

a ten-year-old. I didn’t know.

He spins across the marketplace

all shattered chest, all eyes and arms.

Do I tell her that? Not yet,

though one day I will have

no choice except to tell her

or to send her into the world

wide-eyed and ignorant.

The boy spins across the years

till he lands in a heap

in another war in another place

where yet another generation

is rudely about to discover

what their fathers never told them.

Praying at the Altar

I like pagodas.

There’s something—I don’t know--

secretive about them,

soul-soothing, mind-easing.

Inside, if only for a moment,

life’s clutter disappears.

Once, long ago, we destroyed one:

collapsed the walls

‘til the roof caved in.

Just a small one, all by itself

in the middle of nowhere,

and we were young. And bored.

Armed to the teeth.

And too much time on our hands.

Now whenever I see a pagoda,

I always go in.

I’m not a religious man,

but I light three joss sticks,

bow three times to the Buddha,

pray for my wife and daughter.

I place the burning sticks

in the vase before the altar.

In Vung Tau, I was praying

at the Temple of the Sleeping Buddha

when an old monk appeared.

He struck a large bronze bell

with a wooden mallet.

He was waking up the spirits

to receive my prayers.

Thank You for Your Service

Yes, of course; it’s what you say these days.

Like genuflecting in a Catholic church.

Like saying “bless you” to a sneeze.

A superstitious reflex, but, of course,

sincere. Or is it just to ease the guilt

of sending someone else to do

the dirty work? Whatever. I just say,

“You’re welcome,” let it go at that,

when what I’d really like to say is,

“Thank you for my fucking service

in that fucking war I’ve dragged

from day to day for fifty fucking years

like a fucking corpse that won’t stay dead?

That fucking nightmare that my

fucking country told me was my fucking

patriotic duty to fight? For what,

exactly, do you think you’re thanking me?

Service to my country? You empty-headed

idiot. You think I want your thanks

for what I did? You shallow, superficial

twit. You’ve no idea what I did, or why,

or what it cost a people who had

never done us any harm nor ever

would or could. You can take your

thank you for my service, shove it

where the sun doesn’t shine.”

But you wouldn’t understand.

You’d only get insulted if I told you

what I’d really like to say. So I just say,

“You’re welcome.” Smile. Walk away.

Celebrating the New Year 1968/1969

1.

We were bar-hopping in Hiroshima--

a strange and ghostly place,

nothing standing older than twenty-three years,

the whole city obliterated

by the first atomic attack,

scars on the hills around the city visible still.

Peace gas, Peace cigarettes, Peace candy bars:

white dove logos just about everywhere.

We’d been to the Peace Park already

where the only reinforced concrete structure

surviving the blast still stood,

a hollow, ghostly skeleton,

and the guestbook signed by visitors;

someone had written “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

A fellow American, no doubt.

2.

But we were here tonight

to celebrate the New Year:

Fat Pat, Smitty, the Big Swede, and me.

God only knows what the locals thought of us,

but they liked our money

and we didn’t make any trouble.

Somewhere along the way, we picked up

a bunch of young Norwegians,

merchant seamen, their freighter in port.

When the bars finally closed,

they invited us back to the Arthur Stove

and the party went on from there.

I remember beer, and a table loaded with food,

and a string of little paper Norwegian flags.

We somehow must have gotten some sleep,

but I don’t remember how.

3.

I do remember stopping at Miyajima

on our way back to base the next day:

the Great Torii rising out of the bay,

the floating Shrine of Itsukushima,

the Five-storied Pagoda,

Sika deer by the hundreds,

gentle as house pets, unafraid.

And the women in all their New Year glory,

finest kimonos to start the year off right,

hiding their smiles behind their elaborate fans,

two little girls in kimonos, sisters perhaps,

so impossibly cute you wanted

to curl them up in your arms

and take them home to your Mom.

How I Became an American War Hero

Navy Combat Action Ribbon:

for getting shot at

Purple Heart Medal:

for getting hit

National Defense Service Medal:

for behaving myself for ninety days

Good Conduct Medal:

for behaving myself for three years

Republic of Vietnam Service Medal:

thank you for being in our war (from the US government)

Vietnamese Campaign Medal:

thank you for being in our war (from the Saigon government)

Presidential Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Cross of Gallantry Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Civic Action Meritorious Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Rifle Expert Badge:

for hitting a paper target with a rifle

Pistol Sharpshooter Badge:

for hitting a paper target with a pistol

The Night You Returned

A road crew was paving the highway

the night you returned from the war.

It was March; they had set up floodlights;

the black viscous tar steamed in the cold.

The workmen didn’t notice you.

Why would they?

You weren’t any different

from all the other passersby that night

or any other night, just another car.

They had a machine;

they were laying macadam

mile after mile.

Black. Viscous. Steaming.

Mile after mile after mile.

Deep into the night.

God, Guns & Ginny

Well, of course it was righteous.

Bear any burden, pay any price,

what you could do for your country.

Godless communists, after all.

You may have been only seventeen,

but you’d seen them already

in Hungary, Cuba, Berlin.

Something had to be done,

and someone would have to do it.

There is something about a thatched-roof

hut in the middle of rice fields, burning,

a mortally wounded woman softly

keening, child dead in her arms,

that can’t be blamed on Chairman Mao,

Castro, Lenin, or Das Kapital.

Heavy artillery flattened that home.

Ours. Our guns did that.

Long before I reached my thirteen months,

I discovered I had nothing to cling to

but a girl back home. A young girl.

Still in high school. Watching her friends

go out on dates, having fun, enjoying

all of the things that seniors do

for the last exuberant time together.

She must have agonized for months

before she sent me that final letter.

I hope she’s had a nice life. I mean it.

W.D. Ehrhart kindly accepted the invitation to be our first featured poet, and he has selected the above poems as representative of his work. All have been previously published and are presented here in their original forms.

"Souvenirs," “Guerrilla War,” “Making the Children Behave,” “Guns,” “Praying at the Altar,” and “Thank You for Your Service” are from Ehrhart’s Thank You for Your Service: Collected Poems (McFarland & Co., Inc., 2019).

“Celebrating the New Year,” “How I Became an American War Hero,” “The Night You Returned,” and “God, Guns & Ginny” are from Ehrhart’s Wolves in Winter (Between Shadows Press, 2021).

W.D. Ehrhart's Vietnam Poetry

Guerrilla War

It’s practically impossible

to tell civilians

from the Viet Cong.

Nobody wears uniforms.

They all talk

the same language

(and you couldn’t understand them

even if they didn’t).

They tape grenades

inside their clothes,

and carry satchel charges

in their market baskets.

Even their women fight.

And young boys.

And girls.

It’s practically impossible

to tell civilians

from the Viet Cong.

After awhile,

you quit trying.

Souvenirs

“Bring me back a souvenir,” the captain called.

“Sure thing,” I shouted back above the amtrac’s roar.

Later that day,

the column halted,

we found a Buddhist temple by the trail.

Combing through a nearby wood,

we found a heavy log as well.

It must have taken more than half an hour,

but at last we battered in

the concrete walls so badly

that the roof collapsed.

Before it did,

I took two painted vases

Buddhists use for burning incense.

One vase I kept,

and one I offered proudly to the captain.

Making the Children Behave

Do they think of me now

in those strange Asian villages

where nothing ever seemed

quite human

but myself

and my few grim friends

moving through them

hunched

in lines?

When they tell stories to their children

of the evil

that awaits misbehavior,

is it me they conjure?

Guns

Again we pass that field

green artillery piece squatting

by the Legion Post on Chelten Avenue,

its ugly little pointed snout

ranged against my daughter’s school.

“Did you ever use a gun

like that?” my daughter asks,

and I say, “No, but others did.

I used a smaller gun. A rifle.”

She knows I’ve been to war.

“That’s dumb,” she says,

and I say, “Yes,” and nod

because it was, and nod again

because she doesn’t know.

How do you tell a four-year-old

what steel can do to flesh?

How vivid do you dare to get?

How explain a world where men

kill other men deliberately

and call it love of country?

Just eighteen, I killed

a ten-year-old. I didn’t know.

He spins across the marketplace

all shattered chest, all eyes and arms.

Do I tell her that? Not yet,

though one day I will have

no choice except to tell her

or to send her into the world

wide-eyed and ignorant.

The boy spins across the years

till he lands in a heap

in another war in another place

where yet another generation

is rudely about to discover

what their fathers never told them.

Praying at the Altar

I like pagodas.

There’s something—I don’t know--

secretive about them,

soul-soothing, mind-easing.

Inside, if only for a moment,

life’s clutter disappears.

Once, long ago, we destroyed one:

collapsed the walls

‘til the roof caved in.

Just a small one, all by itself

in the middle of nowhere,

and we were young. And bored.

Armed to the teeth.

And too much time on our hands.

Now whenever I see a pagoda,

I always go in.

I’m not a religious man,

but I light three joss sticks,

bow three times to the Buddha,

pray for my wife and daughter.

I place the burning sticks

in the vase before the altar.

In Vung Tau, I was praying

at the Temple of the Sleeping Buddha

when an old monk appeared.

He struck a large bronze bell

with a wooden mallet.

He was waking up the spirits

to receive my prayers.

Thank You for Your Service

Yes, of course; it’s what you say these days.

Like genuflecting in a Catholic church.

Like saying “bless you” to a sneeze.

A superstitious reflex, but, of course,

sincere. Or is it just to ease the guilt

of sending someone else to do

the dirty work? Whatever. I just say,

“You’re welcome,” let it go at that,

when what I’d really like to say is,

“Thank you for my fucking service

in that fucking war I’ve dragged

from day to day for fifty fucking years

like a fucking corpse that won’t stay dead?

That fucking nightmare that my

fucking country told me was my fucking

patriotic duty to fight? For what,

exactly, do you think you’re thanking me?

Service to my country? You empty-headed

idiot. You think I want your thanks

for what I did? You shallow, superficial

twit. You’ve no idea what I did, or why,

or what it cost a people who had

never done us any harm nor ever

would or could. You can take your

thank you for my service, shove it

where the sun doesn’t shine.”

But you wouldn’t understand.

You’d only get insulted if I told you

what I’d really like to say. So I just say,

“You’re welcome.” Smile. Walk away.

Celebrating the New Year 1968/1969

1.

We were bar-hopping in Hiroshima--

a strange and ghostly place,

nothing standing older than twenty-three years,

the whole city obliterated

by the first atomic attack,

scars on the hills around the city visible still.

Peace gas, Peace cigarettes, Peace candy bars:

white dove logos just about everywhere.

We’d been to the Peace Park already

where the only reinforced concrete structure

surviving the blast still stood,

a hollow, ghostly skeleton,

and the guestbook signed by visitors;

someone had written “Remember Pearl Harbor.”

A fellow American, no doubt.

2.

But we were here tonight

to celebrate the New Year:

Fat Pat, Smitty, the Big Swede, and me.

God only knows what the locals thought of us,

but they liked our money

and we didn’t make any trouble.

Somewhere along the way, we picked up

a bunch of young Norwegians,

merchant seamen, their freighter in port.

When the bars finally closed,

they invited us back to the Arthur Stove

and the party went on from there.

I remember beer, and a table loaded with food,

and a string of little paper Norwegian flags.

We somehow must have gotten some sleep,

but I don’t remember how.

3.

I do remember stopping at Miyajima

on our way back to base the next day:

the Great Torii rising out of the bay,

the floating Shrine of Itsukushima,

the Five-storied Pagoda,

Sika deer by the hundreds,

gentle as house pets, unafraid.

And the women in all their New Year glory,

finest kimonos to start the year off right,

hiding their smiles behind their elaborate fans,

two little girls in kimonos, sisters perhaps,

so impossibly cute you wanted

to curl them up in your arms

and take them home to your Mom.

How I Became an American War Hero

Navy Combat Action Ribbon:

for getting shot at

Purple Heart Medal:

for getting hit

National Defense Service Medal:

for behaving myself for ninety days

Good Conduct Medal:

for behaving myself for three years

Republic of Vietnam Service Medal:

thank you for being in our war (from the US government)

Vietnamese Campaign Medal:

thank you for being in our war (from the Saigon government)

Presidential Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Cross of Gallantry Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Civic Action Meritorious Unit Citation:

for randomly getting assigned to 1st Battalion, 1st Marines

Rifle Expert Badge:

for hitting a paper target with a rifle

Pistol Sharpshooter Badge:

for hitting a paper target with a pistol

The Night You Returned

A road crew was paving the highway

the night you returned from the war.

It was March; they had set up floodlights;

the black viscous tar steamed in the cold.

The workmen didn’t notice you.

Why would they?

You weren’t any different

from all the other passersby that night

or any other night, just another car.

They had a machine;

they were laying macadam

mile after mile.

Black. Viscous. Steaming.

Mile after mile after mile.

Deep into the night.

God, Guns & Ginny

Well, of course it was righteous.

Bear any burden, pay any price,

what you could do for your country.

Godless communists, after all.

You may have been only seventeen,

but you’d seen them already

in Hungary, Cuba, Berlin.

Something had to be done,

and someone would have to do it.

There is something about a thatched-roof

hut in the middle of rice fields, burning,

a mortally wounded woman softly

keening, child dead in her arms,

that can’t be blamed on Chairman Mao,

Castro, Lenin, or Das Kapital.

Heavy artillery flattened that home.

Ours. Our guns did that.

Long before I reached my thirteen months,

I discovered I had nothing to cling to

but a girl back home. A young girl.

Still in high school. Watching her friends

go out on dates, having fun, enjoying

all of the things that seniors do

for the last exuberant time together.

She must have agonized for months

before she sent me that final letter.

I hope she’s had a nice life. I mean it.

W.D. Ehrhart kindly accepted the invitation to be our first featured poet, and he has selected the above poems as representative of his work. All have been previously published and are presented here in their original forms.

"Souvenirs," “Guerrilla War,” “Making the Children Behave,” “Guns,” “Praying at the Altar,” and “Thank You for Your Service” are from Ehrhart’s Thank You for Your Service: Collected Poems (McFarland & Co., Inc., 2019).

“Celebrating the New Year,” “How I Became an American War Hero,” “The Night You Returned,” and “God, Guns & Ginny” are from Ehrhart’s Wolves in Winter (Between Shadows Press, 2021).

Bio: W. D. Ehrhart was born in 1948 and grew up in Perkasie, Pennsylvania. After graduating from Pennridge High School in 1966, he enlisted in the US Marine Corps at age 17, serving three years including 13 months in Vietnam, earning the rank of sergeant and receiving the Purple Heart, the Navy combat Action Ribbon, and a 1st Marine Division Commanding General’s Commendation. He has since earned a Bachelor of Arts from Swarthmore College, a Master of Arts from the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle, and a Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Wales at Swansea, UK.

In his 20s and early 30s, he worked a variety of jobs including construction worker, forklift operator, newspaper reporter, magazine writer, merchant seaman, and legal assistant for the Pennsylvania Department of Justice Office of the Special Prosecutor. He taught sporadically at three Friends Schools and several colleges, as well as holding an appointment as Visiting Professor of War & Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts at Boston, but recently retired after 18 years as a Master Teacher of English & History at the Haverford School for Boys.

Over the years, Ehrhart has been awarded a Mary Roberts Rinehart Grant, two Fellowships from the Pennsylvania Arts Council, the President’s Medal from Veterans for Peace, a Pew Fellowship in the Arts, and an Excellence in the Arts Award from Vietnam Veterans of America. His writing has appeared in hundreds of publications ranging from the American Poetry Review, North American Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Utne Reader to USA Today, Reader’s Digest, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times.

WDEhrhart.com

In his 20s and early 30s, he worked a variety of jobs including construction worker, forklift operator, newspaper reporter, magazine writer, merchant seaman, and legal assistant for the Pennsylvania Department of Justice Office of the Special Prosecutor. He taught sporadically at three Friends Schools and several colleges, as well as holding an appointment as Visiting Professor of War & Social Consequences at the University of Massachusetts at Boston, but recently retired after 18 years as a Master Teacher of English & History at the Haverford School for Boys.

Over the years, Ehrhart has been awarded a Mary Roberts Rinehart Grant, two Fellowships from the Pennsylvania Arts Council, the President’s Medal from Veterans for Peace, a Pew Fellowship in the Arts, and an Excellence in the Arts Award from Vietnam Veterans of America. His writing has appeared in hundreds of publications ranging from the American Poetry Review, North American Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Utne Reader to USA Today, Reader’s Digest, the Los Angeles Times, and the New York Times.

WDEhrhart.com

Except where otherwise attributed, all pages & content herein

Copyright © 2014 - 2024 Paul Hellweg VietnamWarPoetry.com All rights reserved

Westerly, Rhode Island, USA